Quantifying the Divide

Charting Disparities in Los Angeles’ Housing Crisis

Public policy experts, housing advocates and local politicians alike warn that inequities in the housing landscape are outpacing the state’s efforts to curb homelessness and upscale housing production. This data dashboard dives into those imbalances in Los Angeles — charting housing costs, development, evictions, homelessness, and analyzing Sacramento’s strategy to even the scales.

By Gavin J. Quinton

It hasn’t even been a year since Martha Yurel and dozens of her neighbors were evicted from the Maui Apartments in Burbank.

She lived there for more than 11 years and was never late on rent. She didn’t violate her lease, and never seriously damaged the property. Burbank was where she raised her kids, and now, at 63 years old, its where she planned to retire to watch her grandchildren grow up. But a no-fault eviction threw a wrench in those plans.

Yurel and more than 20 of her neighbors received the 60 day notice to vacate. Landlords posted thousands more like it throughout the region in the months following the end of the pandemic-era eviction moratorium. Taking advantage of a legal loophole in state tenant protection law, landlords like Yurel’s — who claim they intend to renovate a property — are able to oust tenants, flip their units and greatly increase the asking rent price for that home.

Instead of going quietly, Yurel fought. She organized her neighbors, unionized, protested, lawyered up, marched on City Hall and got local law changed. It wasn’t enough to stop the eviction. Yurel was uprooted and priced-out of her home, but she’s still lobbying the city to pass stricter eviction protections for tenants to prevent what happened to her from happening to others.

Data shows that Yurel’s experience is common in Los Angeles. Last year, 77,049 eviction notices were filed. 91% of those were 3-day notices. And while most evictions were for nonpayment of rent, the average balance owed was just $3,774. A recent UCLA study found more than half of all renters in Los Angeles County are rent burdened, spending over 50% of their income in rent.

High rents, soaring eviction rates and homelessness are all symptoms of California’s housing shortage, experts say. State estimates place the shortage at about 3-4 million units, or about a quarter of California's housing stock. And while Sacramento has taken a hardline policy approach to incentivize housing development, some housing advocates say lawmakers’ response to the shortage is underfunded and reactionary.

Soaring Housing Prices in a Teetering Economy

Housing shortage, combined with nationwide lulls in income growth, puts California at the second-highest home price-to-income ratio. California has a median home price of $765,197 and a median household income of $91,551, so the state’s price-to-income ratio is 8.4%

Housing market data collected by Harvard University (visualized in the map to the above) shows the extent to which home prices have soared relative to incomes in a growing number of metro areas since 1980. Of the 10 highest price-to-income ratios in the country, eight are California metros.

Price-to-income ratios reached all-time highs in 78 of the nation’s 100 largest markets in 2022. Of those, only Syracuse, New York had a price-to-income ratio under 3.0, which was the norm across much of the country in prior decades. Two-thirds of large markets had price-to-income ratios below 3.0 in 2000, according to the study.

The housing shortage, combined with stagnate wages, has created market conditions that leave about a third of California renters severely rent-burdened.

“We have this weird paradox in California where our renter population is actually relatively high-income compared to a lot of other states, but at the same time, we have more people who are facing financial stress and overwhelming rental costs,” said Eric McGhee, a demography expert for the Public Policy Institute of California.

According to McGhee, even high income renters are rent burdened, but those lower on the income scale are more likely to be priced from their homes to cheaper markets, face evictions or become homeless.

“The way to square those two findings is that we have a lot of higher income people who are renting than we would in the past. Because we're not building enough housing to accommodate that demand, a lot more high-income people are sort of trapped in the renter market, even though they might want to move over into the owner market,” McGhee said.

The increased pressure of higher income renters drives up rent prices, making the market more difficult to navigate for people further down the income scale. This sets the bar for people who are deeply stressed and don't really have anywhere else they can go, McGhee said.

Evictions: Landlords and Tenants Share Experiences

Martha Yurel pickets outside of city hall ahead of a City Council meeting regarding tenant protection measures.

Until last year, there were no reliable data for yearly evictions in California. This is because, apart from a handful of cities like Berkley, Oakland and Richmond, cities do not track evictions, nor do they require landlords to file with the city when they post a notice.

Once an eviction notice is posted, it doesn’t often result in a court ordered unlawful retainer. This means most evictions are not documented in any measurable way, which has led some experts to speculate the number of yearly is evictions is much higher than estimates

Charting the Course

While cities throughout the state struggle to prioritize extensive development against resistance from residents, advocates are fighting for tenant protections to alleviate the financial burdens of still record-breaking housing costs.

In Burbank, that’s exactly what Yurel was working toward. Her goal, along with the members of the Burbank Tenants Union, is to eliminate renovation evictions for good from the city, a move other municipalities adopted from as early as 2018.

Tenants marched from the Maui apartments, over the Olive Avenue Bridge to city hall to call for protections. In September, Yurel and her neighbors succeeded in pressuring the Burbank City Council to pass an ordinance placing additional requirements on owners who intend to evict tenants to make substantial remodels to their units, not outright barring renovation evictions, but making them costlier.

It still wasn’t enough. Yurel finally received her eviction notice in November.

“Every day I would go home and wait to see that notice on my door. Months went by with no notice. Then one day I go outside, I turn around and there’s a note on my door. I looked over and there was the guy that was giving more notices to my neighbors. He just looked at me. And I told him I’m fighting this,” Yurel said.

Yurel wasn’t the first of her neighbors to receive an eviction notice. The Maui apartments had passed through a number of hands, purchased from its original owner in 2019 and then purchased again by a Beverly Hills-based LLC, Olive Apartments in March 2023.

“Come April, I see some neighbors outside with a piece of paper,” Yurel said. “I said ‘what’s that?’ The notice of eviction. My heart sank. And I told my daughter this is not going to happen to me like this. We aren’t going to let them do this to us. We’re gonna fight.”

Yurel began organizing with her neighbors alongside the Burbank Tenant’s Union. One neighbor called her the Erin Brockovich of the Maui Apartments.

Tenant Emmanuel Perez reviews a 60-day notice to vacate his apartment.

This was the case with Yurel’s eviction. It is legal in California for a landlord to evict a tenant if they plan to renovate a property. But the actual renovations are not enforced in most cities, meaning landlords can simply site an “intent” to renovate, push out their tenants, and relist the property for more.

“When a tenant’s [rent] is low, the value of the building is directly attached to the income that the building generates. So when it comes to refinancing or selling the property, their property is not worth as much as the other [comparable] ones. So business wise, it doesn’t make sense whatsoever for any landlord to keep tenants that are paying below the market value,” Khodaverdian said.

Homelessness On the Rise

Recently, Los Angeles Controller Kenneth Mejia collected data from the Los Angeles Courts to quantify formal eviction filings in 2023. Those 77,046 evictions have been mapped in the chart to the right. Of those evictions, 96% cited non-payment of rent, and the average due rent balance was $3,774.

The lack of available affordable housing is the primary cause of homelessness in California, according to a recent study by the University of California San Francisco, which surveyed and interviewed more than 3,500 unhoused individuals.

“In California, more than 171,000 people experience homelessness daily. California is home to 12% of the nation’s population, 30% of the nation’s homeless population, and half the nation’s unsheltered population,” according to the study, which found that the homeless population is aging, and Black, Latino, and Indigenous people are are overrepresented in the state’s homeless population.

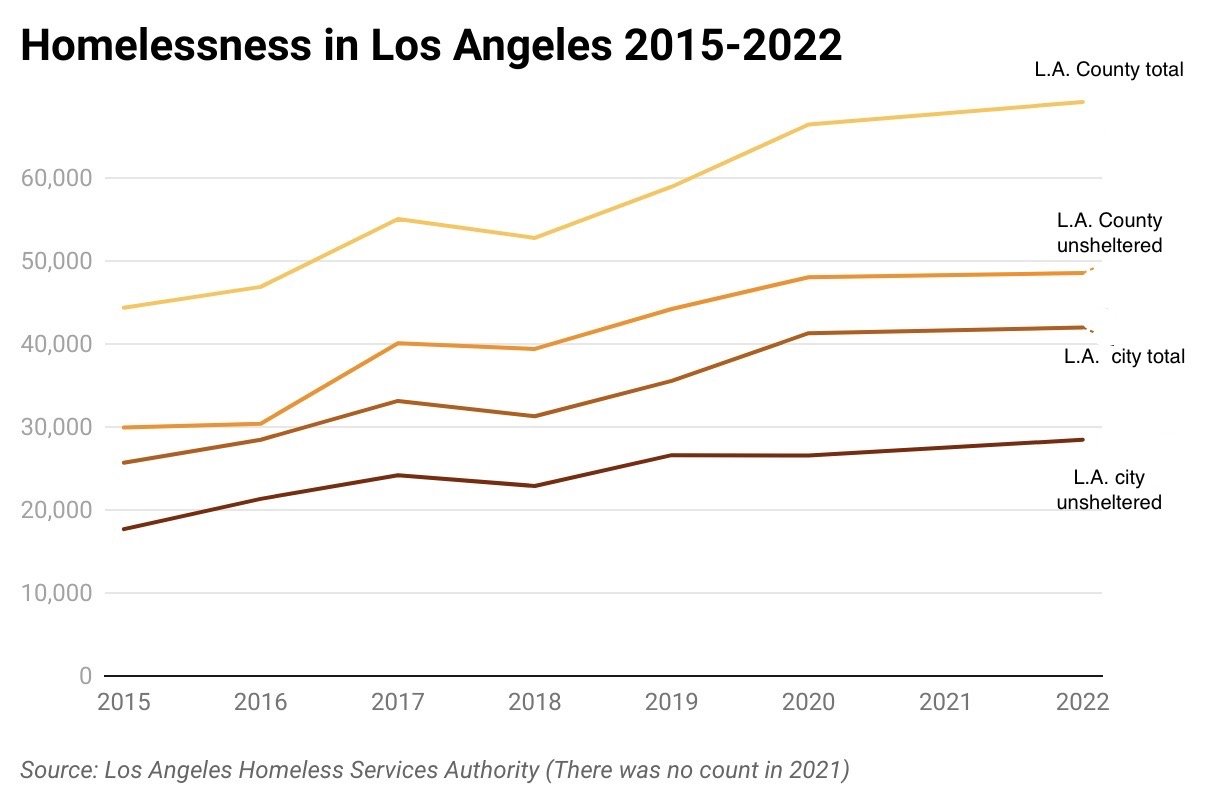

California has been the state with the largest homeless population for more than a decade. The 2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count, a point in time tally of the county’s unhoused population, showed a 9% rise in homelessness on any given night in Los Angeles County to an estimated 75,518 people and a 10% rise in the City of Los Angeles to an estimated 46,260 people. The figures show a steady growth trend of people experiencing homelessness, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

“The homeless count results tell us what we already know — that we have a crisis on our streets, and it’s getting worse,” said Dr. Va Lecia Adams Kellum, Chief Executive Officer of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. “The important thing to take away from today is that for the first time, the city, county, and LAHSA are moving with urgency to house the people living on our streets.”

Policymakers Fast Track Development as a Solution

Sacramento’s strategy to quell the housing and rental markets to this point has been to streamline development and consolidate control away from local municipalities.

For starters, lawmakers mandated an easy path to ministerial approval for homeowners who wish to convert accessory dwelling units, also called in-law units, into additional housing with hopes that homeowners jump on the opportunity to expand their properties into rental investments.

Later, the state established housing quotas that cities must meet during a 7-year period, called a housing element.

She made copies of everyone’s notices, began keeping an extensive record of all interactions with the new landlord and their management company and checking with the city for permits at the building.

“Everybody was scared. Nobody knew what to do. So I volunteered as the one to be the contact, because I was upset too, and because I knew we were going to be next,” Yurel said.

Alissandra Valdez, a member of the Burbank Tenant’s Union, said that mass evictions disproportionally affect the most vulnerable members of the community.

“We receive so many emails from seniors and working class single parents who feel like the city has turned its back on them. These incidents are not isolated. They are systemic and currently allowed by the city,” she said.

Another tenant, Cate Cundiff, was evicted from her single-family home after her landlord raised the rent by 13%. This came just days after her and her husband refused to allow their garage to be converted into an Airbnb. She said the move cost her more than $15,000 in total.

“That’s $15,000 further away from home ownership we now are because of a no fault eviction without just cause. Not only has the financial toll been a huge hit on our family, but the mental toll has been devastating,” Cundiff said, adding that her five-year-old daughter feared their home would be torn down. “No five-year-old should have to worry about losing their home.”

One L.A. landlord, Harry Timuryan, said that the COVID-19 pandemic and eviction moratorium was devastating for landlords.

“It’s been a difficult and weird six years. Inflation has gone up tremendously, materials costs have gone up and the pandemic was disastrous for housing providers. At that time, [property owners] were left out of conversation,” Timuryan said. “So, if you ask a housing provider if they have breathing room, the answer is absolutely not, especially not on the tail of those challenges,” he said.

Timuryan said that, in addition to rising costs, his biggest fear is the uncertainty of local policy changes, like the city adding new rent control measures or additional red tape for evictions.

“No one wants to do an eviction. Its costly for a housing provider too, to have to go through that,” Timuryan said.

One property owner, Masis Khodaverdian, has served four eviction notices in L.A. since 2023. He said that he typically has good relationships with his tenants and has no problems. Sometimes though, tenants can’t pay rent or cause excessive damage to the property, he said, and eviction becomes necessary.

Other times though, an eviction makes sense from a business perspective, he said.

Rent Costs Accelerate as Wages Remain Stagnate

Changes in Rent VS. Income Growth in the U.S. , 2001-2015

“They can't move somewhere else, because they're already in the lowest-income areas. So they just end up paying that rent, and it's hard for them. In some cases, people get evicted. They end up homeless,” McGhee said. “It's a ripple effect that spreads down from a housing market that isn't producing enough housing to meet the demand for buying.”

From 2010 to 2020, the state’s population grew 6.1% while its housing inventory rose by just 4.7%, and since then, cities across California have only built about half of the 180,000 new units needed to alleviate market pressures.

As a result, the state mandated Senate Bill 35, stripping local control away from municipalities that fail to meet their housing development quotas. Under the bill, cities must approve any development that has at least 10% affordable units as long as the project meets zoning and land-use requirements. In some cases, parking and density requirements are waved, leading to ultra-dense developments of 100 or more units, sometimes with fewer than seven parking spaces.

“The state has implemented all kinds of policies to try to encourage housing and the fundamental tension is over local control,” said Hans Johnson, a senior fellow and demography expert at the Public Policy Institute of California.

Johnson said that the solution to the housing crisis may not be what's best for the people who live near new development, but the evidence suggests that increasing the state’s housing inventory will alleviate prices and reduce homelessness and eviction.

“My 30,000 foot view is that there is progress being made. I do think the state’s plan has made a difference. There have been substantial increases in new infill housing in urban core cities in California.”

The catch, Johnson said, is that new development is by far made to rent, not to own.

“Most of the new housing is one bedroom more or less. The vast majority are two bedrooms or less. So its not going to be families that are moving into them. So our study looked at ways to encourage more of those units to be able to be available for homeownership, and for more of them to be three bedrooms, so that they were amenable to families,” Johnson said.

Ultimately, Johnson said the state’s strategy has been effective, but lawmakers are still eyeing new ways to foster an economy that works for the lower class.

That's what Nick Schultz ran on, he recently won the primary election for the 44th District Assembly seat, representing a handful of Los Angeles municipalities.

He said that, so far, the state’s mandates have worked, but they only come with consequences for cities that don’t meet requirements.

“We need to continue the push for not only requirements, but incentives and rewards for local jurisdictions that are adding the intelligent infill housing that we need, and it needs to be truly affordable housing development, not just market rate,” Schultz said.

He added that constructs like social housing, increased public transportation can also move the needle on creating a more equitable housing market, and said that, in the meantime, legislators should also focus on expanding renter protections to ensure tenants don’t fall into homelessness before the rental market sees relief.

“I think when we talk about the housing crisis, we have to look at it holistically and across multiple issues,” Schultz said. “I don't think we can be narrow minded in the legislature and say, well, we just need more housing, and that solves it. If the plan is not centered around the people that need it the most in our community, it, too, will fail.”

The interactive map to the left displays California cities with geo-markers scaled based on how many new housing units that city has produced since 2018. The City of Los Angeles has a massive housing production goal of 456,643. From the period of 2018 to the present day, Los Angeles has built 105,260 new housing units.

The graph below displays cities within Los Angeles county in order of their progress to state housing goals. Cities like Baldwin Park haven’t built a single unit, while Sierra Madre has more than doubled expected supply.

Tenants march over the Olive Avenue Bridge ahead of a Burbank City Council meeting Aug. 8.

Martha Yurel stands in her new apartment in North Hollywood.

Yurel still meets with the Burbank Tenants Union, which continues to lobby the city for additional tenant protection measures. They recently succeeded in organizing more than 50 tenants to speak during a Council meeting, which resulted in the body voting to pursue renovation eviction protections, legal aid for tenants and landlords, and a study on rent control.

She moved from her one-bedroom apartment in Burbank to North Hollywood where she shares a smaller flat with a roommate.

“I lost the battle for my own home, so now I’m fighting for the future. For my grandkids and for all of the seniors and workers who have no other options,” Yurel said.